⚰️ One of the Unhappiest Gaming Experiences of your C64 life?

Dan Tootill remembers a game with “an air of death about it”… With Halloween approaching, what could be more fun than recalling one of those Commodore 64 games that gave […]

Commodore Format magazine fan site

Dan Tootill remembers a game with “an air of death about it”… With Halloween approaching, what could be more fun than recalling one of those Commodore 64 games that gave […]

Dan Tootill remembers a game with “an air of death about it”…

With Halloween approaching, what could be more fun than recalling one of those Commodore 64 games that gave me the creeps when I was young lad? Even in the 8-bit era, there were one or two games that were genuinely a bit scary… but let’s skip right over the obvious ones. I find it more interesting to delve into a game that was unintentionally creepy, and if you hadn’t already guessed, I am talking about a budget game called The Happiest Days of Your Life.

Released by Firebird in 1986 as part of their hugely diverse £1.99 range, the game throws you into the ill-fitting shoes of one G. McFat, a hapless schoolboy accused of stealing the head teacher’s wallet, who must hunt down and return it in order to clear his name. He must also secure some “photographic evidence” according to the instructions, presumably of the missing wallet or the person who really took it, but this statement is a tad ambiguous (more on that later).

I was always a sucker for flick-screen arcade adventures, so I wasted no time in adding this to my collection for a mere two quid. I was hoping the Skool Daze energy conveyed by the cover art would carry through into the game but no such luck, in fact the bustling, brightly-lit corridors of Eric’s old school were a haven compared to the nightmare world in which this game was set. I kid you not, Happiest Days has you skulking around a seemingly derelict town in what feels like the dead of night, performing a series of cryptic tasks by moving random objects from one location to another, as was the style at the time. The gameplay leaned heavily to the dull side but that wasn’t my real issue with this game. There was something else, something disconcerting and weird.

Far more than a little inspiration was drawn from Everyone’s a Wally, verging on plagiarism in fact, as the screen layout, swap-and-carry system and even some locations are nigh on identical. The post office, garden shed (workshop) and Elm Walk (park) screens are redrawn versions of the same locations from the Mikro-Gen game but considering the game’s price label back then, we told ourselves this was sort of okay. The big difference here is that the Wally series (themselves borrowing heavily from Jet Set Willy) were charming in their own way, despite their similarly dark backgrounds, imposing locations and the titular character being not so easy on the eye. I spent countless hours pacing around Wally’s neighbourhood, trying to find whichever of those cretins who had wandered off with the fuse wire, and it was joyous. In contrast, the landscape in Happiest Days felt desolate, abandoned and lonely.

The first time I loaded the game, I began to feel a little uneasy after a few minutes but I couldn’t quite put my finger on why that was. I did my best to dismiss this feeling but it would resurface each time I played it, with the puzzles appearing to make less sense the more of them I solved. On one occasion, my older brother was hovering over my shoulder and despite not being much of a gamer himself, he would often have something to say about my choice of software. I hadn’t breathed a word about the game myself at this point, but I turned to find him screwing up his nose in disapproval.

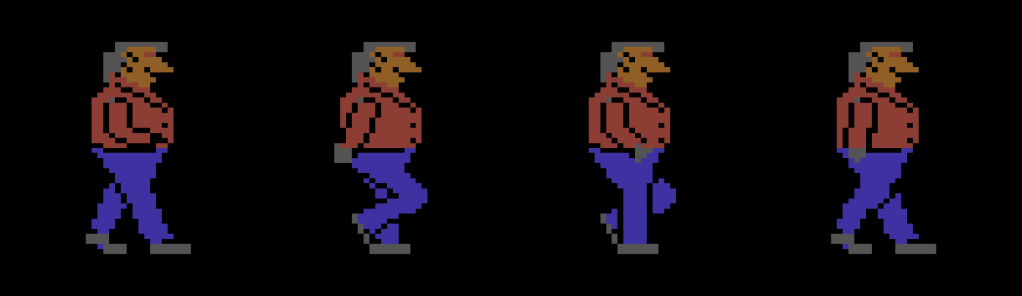

“This game looks really dreary,” he opined. Undoubtedly, there was something off about the game and he had picked up on it immediately. “Don’t tell me you have to play as that guy the whole time,” he continued, pointing to the gangly triple-sprite that was the main character. I nodded, as the bloated, orange-faced figure lurched unnaturally across the screen under my control.

“He doesn’t add much to the game does he?” I laughed.

“Depression,” my brother scoffed. “He adds depression to the game” and he left the room rather than watch me play it any longer. It was now obvious that the game was just that, it was depressing and I began to wonder if its title might have been chosen ironically. Visiting screens with names like “Dingy Nightclub”, “Ruined Chapel”, “Crumbling Tower” and “The Crypt” didn’t exactly help to lighten the mood. Before long, I felt my desire to solve more puzzles outweighed by the urge to flick the power switch off. In fact, I would have to play something else for a few minutes just to counteract the sense of melancholy. I don’t think I can say that about any other game on the Commodore 64, apart from those CRL text adventures maybe. What was it about this game’s atmosphere that was so off-putting? Was it the looming silhouette of a man behind the door on the loading screen, contrasting against the absence of any other human characters in the actual game? Even after all these years I can’t figure out what drives this sense of foreboding, but this is undoubtedly the game’s stand-out feature. There is no greater level of creepiness than the kind you can’t properly explain, and part of me loves this game because of it.

There is an odd mix of high-res and multicolour mode graphics, as if the programmer set out to draw all new graphics for the Commodore version and then ended up copying a bunch of assets from the ZX Spectrum version to save time, but this is merely speculation. Since the player sprite has no jump animation, the frames of his walk cycle are shown while jumping and it looks goofy as heck. Worse still, the position of his legs doesn’t match the swing of his visible arm, suggesting the sprites were assembled in the wrong order and the end result is like an egg beater with a gruesome red-eyed face drawn on it.

I decided to revisit the game in 2023 out of nought but morbid curiosity, and I have to say the effect was pretty much the same. However, I dug far enough into the game to make it all the way to the end and made a surprising discovery in doing so. The Commodore 64 version of the game is in fact quite broken, by that I mean one can complete it by solving just a fraction of the puzzles set out in the game’s code. For example, the ZX Spectrum version requires the player to place a telephone at the other end of the machine that appears in the “Barred Out” screen before you can pick up the battery, while in the C64 version this machine doesn’t even appear and you can just pick the battery up. As such, the majority of the objects found throughout the game serve no purpose despite many of them appearing to have a positive function, which just confuses things further! When you go to dig up the head’s wallet, the game doesn’t check to see if you’re carrying the trowel so you don’t need to solve any of the puzzles required to obtain the trowel. On the plus side, completing it kind of takes the edge off at least, as you can rest assured that the end sequence doesn’t reveal that McFat has been dead all along and must now return safely to Hell.

The evidence mentioned in the instructions is an object found in the “Dingy Nightclub”, which appears to be a photographic print of two stick figures. It’s difficult to tell from a few square pixels but it would appear to be of a man and a lady, and it doesn’t look like the lady is wearing very much. Perhaps the object of the game is also to frame someone (the head?) with an incriminating photo, and Firebird felt it best not to mention it? Par for the course for this strange game I suppose.

The far more polished ZX Spectrum version is a lot more fun, but still slightly creepy in its own right. Perhaps it’s the gothic font used in that version, perhaps it’s because the skulls found in the sea cave resemble the demon face from The Exorcist, but I digress. On the face of it, Happiest Days on the C64 is just an unfinished knock-off Wally game with all the hallmarks of a time-pressured, low effort budget title, but that’s not what I will remember it for. One Lemon64 user remarked that the game “has an air of death about it”, so I know it wasn’t just me and my brother who thought so. But the burning question is how a simple adventure game set in and around a school could turn into a chilling yet ultimately pointless experience that’s about as pleasant as a fever dream and as uplifting as watching Threads? Hold on, that’s exactly what happened with Grange Hill, so I suppose that just raises further questions!

I’m slightly disappointed that there isn’t some fantastic urban legend surrounding this game, a story of something macabre happening during its development perhaps, that explains why it turned out this way and why nobody seems to know who programmed it. But I suppose the only thing left to do is fire up your C64 or favourite emulator and take old pumpkin face McFat for a stroll through the ruins and darkness yourself. Perhaps your experience will be nothing like the above, or perhaps it will haunt your dreams forever more, as it does mine.

Night night. CF 🎃

You must be logged in to post a comment.